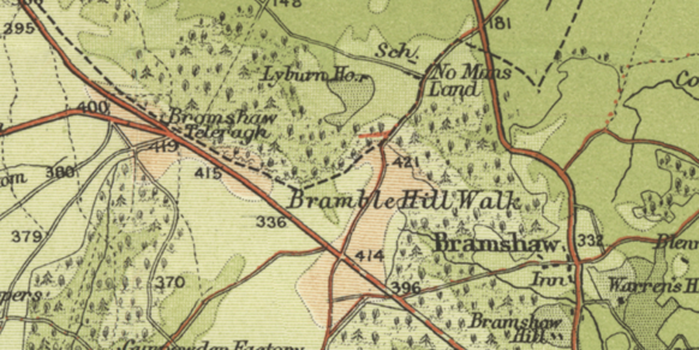

Extract from the 1902 Bartholomew Half Inch Sheet 33 (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

Extract from the 1902 Bartholomew Half Inch Sheet 33 (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland) By Andrew Gustar

In the early 1800s, a message could be sent between Plymouth and London in a matter of minutes. The Admiralty Shutter Telegraph, devised by Lord George Murray during the Napoleonic Wars, consisted of a series of hilltop signalling stations, each manned by a naval officer and two ratings, who sent signals by opening and closing combinations of six shutters in a vertical frame, and monitored signals from neighbouring stations through powerful telescopes. Similar communication lines were in place between the Admiralty and Portsmouth, Deal, Sheerness and Great Yarmouth.[i]

One such telegraph station was in the New Forest, near the village of Bramshaw and about five miles east of Fordingbridge. Ordnance Survey drawings from 1807 show it as “Bramshaw Telegraph”, and the spot, near the junction of the B3080 and the B3078 (grid reference SU227167), is still given this name on modern maps.

In 1902, the Bartholomew Half Inch map, Sheet 33: New Forest & Isle of Wight labelled the location as “Bromshaw Teleragh”. The misprint was corrected in the next edition in 1924.

Ford knew this part of the world well. It was on the itinerary of his walking trip in August 1902, and he and Elsie spent a few months of 1904 staying first at Setley near Brockenhurst in the New Forest, and then at Winterbourne Stoke on Salisbury Plain. He corresponded regularly with W H Hudson, who lived nearby, and in 1910 Ford spent some time in Fordingbridge with Violet Hunt. These locations are all on the Bartholomew Half Inch Sheet 33, and it is quite possible that Ford acquired a copy sometime around 1902-1904.

Ford’s novel The Good Soldier, started at the end of 1913, features Edward and Leonora Ashburnham, who live at Branshaw Manor, a “beautiful, beautiful old house […] just near Branshaw Teleragh” in the neighbourhood of Fordingbridge.[ii] Surely Ford must have got this unusual name from the misprint on the 1902 Bartholomew map. He would have known it was a misprint: the spot was marked correctly on other maps, and it was known locally as Bramshaw Telegraph. Ford might have come across the London to Deal branch of the Murray telegraph when he was researching The Cinque Ports in 1900 (although it is not mentioned).

The nearest large house to the real Bramshaw Telegraph is Lyburn House (now Lyburn Park) a mile to the east, near the village of Nomansland. Lyburn was built in 1822, so it does not have the heritage of the fictional Branshaw Manor, although its setting is consistent with the descriptions in the novel. The narrator, John Dowell, “descended on [the house] from the high, clear, windswept waste of the New Forest” (p.23), and later described it as lying “in a little hollow with lawns across it and pine-woods on the fringe of the dip” (p.86). Lyburn House sits at a shallow col between two small wooded hills, and the route from Bramshaw Telegraph involves a steep path downhill through mixed woodland. This makes Lyburn a better fit than Bramshaw Hill House or Warren’s House (shown on earlier maps as “Bramshaw House”), both of which are further away and set on hillsides.

Ford often bases his fictional locations on real places, and I was delighted to stumble across the misprint that proves that Branshaw Teleragh is no exception. It is ironic that a novel so dependent on what is not said should feature a mistyped placename with its origins in the quest for accurate and efficient communication.

In the second part of this blog post, I will consider some of the people associated with Lyburn Park, who might – perhaps – have influenced the novel.

[i] The telegraph stations became non-operational after 1816, but their legacy lives on in placenames such as “Telegraph Hill”, “Telegraph Wood”, etc. The French had a similar system – the télégraphe Chappe (named after its inventor) – which used semaphore signals of pivoted wooden arms on a fixed mast.

[ii] Whilst most editions of The Good Soldier stick with the “Branshaw” of the first edition, the Norton Critical Edition (1995, 2012) reverts to “Bramshaw”, to which Ford consistently corrected the original manuscript and typescript copies, but which was ignored by the compositor of the first edition. The quote is from p.23 of the Oxford World Classics edition (2012).

In the early 1800s, a message could be sent between Plymouth and London in a matter of minutes. The Admiralty Shutter Telegraph, devised by Lord George Murray during the Napoleonic Wars, consisted of a series of hilltop signalling stations, each manned by a naval officer and two ratings, who sent signals by opening and closing combinations of six shutters in a vertical frame, and monitored signals from neighbouring stations through powerful telescopes. Similar communication lines were in place between the Admiralty and Portsmouth, Deal, Sheerness and Great Yarmouth.[i]

One such telegraph station was in the New Forest, near the village of Bramshaw and about five miles east of Fordingbridge. Ordnance Survey drawings from 1807 show it as “Bramshaw Telegraph”, and the spot, near the junction of the B3080 and the B3078 (grid reference SU227167), is still given this name on modern maps.

In 1902, the Bartholomew Half Inch map, Sheet 33: New Forest & Isle of Wight labelled the location as “Bromshaw Teleragh”. The misprint was corrected in the next edition in 1924.

Ford knew this part of the world well. It was on the itinerary of his walking trip in August 1902, and he and Elsie spent a few months of 1904 staying first at Setley near Brockenhurst in the New Forest, and then at Winterbourne Stoke on Salisbury Plain. He corresponded regularly with W H Hudson, who lived nearby, and in 1910 Ford spent some time in Fordingbridge with Violet Hunt. These locations are all on the Bartholomew Half Inch Sheet 33, and it is quite possible that Ford acquired a copy sometime around 1902-1904.

Ford’s novel The Good Soldier, started at the end of 1913, features Edward and Leonora Ashburnham, who live at Branshaw Manor, a “beautiful, beautiful old house […] just near Branshaw Teleragh” in the neighbourhood of Fordingbridge.[ii] Surely Ford must have got this unusual name from the misprint on the 1902 Bartholomew map. He would have known it was a misprint: the spot was marked correctly on other maps, and it was known locally as Bramshaw Telegraph. Ford might have come across the London to Deal branch of the Murray telegraph when he was researching The Cinque Ports in 1900 (although it is not mentioned).

The nearest large house to the real Bramshaw Telegraph is Lyburn House (now Lyburn Park) a mile to the east, near the village of Nomansland. Lyburn was built in 1822, so it does not have the heritage of the fictional Branshaw Manor, although its setting is consistent with the descriptions in the novel. The narrator, John Dowell, “descended on [the house] from the high, clear, windswept waste of the New Forest” (p.23), and later described it as lying “in a little hollow with lawns across it and pine-woods on the fringe of the dip” (p.86). Lyburn House sits at a shallow col between two small wooded hills, and the route from Bramshaw Telegraph involves a steep path downhill through mixed woodland. This makes Lyburn a better fit than Bramshaw Hill House or Warren’s House (shown on earlier maps as “Bramshaw House”), both of which are further away and set on hillsides.

Ford often bases his fictional locations on real places, and I was delighted to stumble across the misprint that proves that Branshaw Teleragh is no exception. It is ironic that a novel so dependent on what is not said should feature a mistyped placename with its origins in the quest for accurate and efficient communication.

In the second part of this blog post, I will consider some of the people associated with Lyburn Park, who might – perhaps – have influenced the novel.

[i] The telegraph stations became non-operational after 1816, but their legacy lives on in placenames such as “Telegraph Hill”, “Telegraph Wood”, etc. The French had a similar system – the télégraphe Chappe (named after its inventor) – which used semaphore signals of pivoted wooden arms on a fixed mast.

[ii] Whilst most editions of The Good Soldier stick with the “Branshaw” of the first edition, the Norton Critical Edition (1995, 2012) reverts to “Bramshaw”, to which Ford consistently corrected the original manuscript and typescript copies, but which was ignored by the compositor of the first edition. The quote is from p.23 of the Oxford World Classics edition (2012).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed